Charlotte Cotton:

There are so many facets to your artistic practice that, on a material level, see you moving between sculptural and photographic registers and forms that oscillate between surfaces and volumes – 2D image and 3D object – bound inextricably together. You describe your artistic investigations as a movement away from the traditional idea of photography as a monocular vision, where you can draw a direct line from the photographer’s eye, through the camera, to their chosen subject. Instead, your artworks have an ‘omnidirectional’ vantage point – and often a sculptural affect or form. Your works liberate photography from simulating human vision and encourage us to enter another way of seeing. Can you tell me about this and why you think that has been such a through-line in your practice?

Brandon Lattu:

This question is such a challenge to answer because the very premise or definition of photography is so broad now: is it a name for the global distribution of images, the discipline as practiced with cultural reflexivity, or the activity that a majority of the world practices with their phone daily? I think that my suggestion of the omnidirectional quality addresses each of these aspects, but maybe let’s stick to the use with conscious cultural reflexivity – art.

Charlotte Cotton:

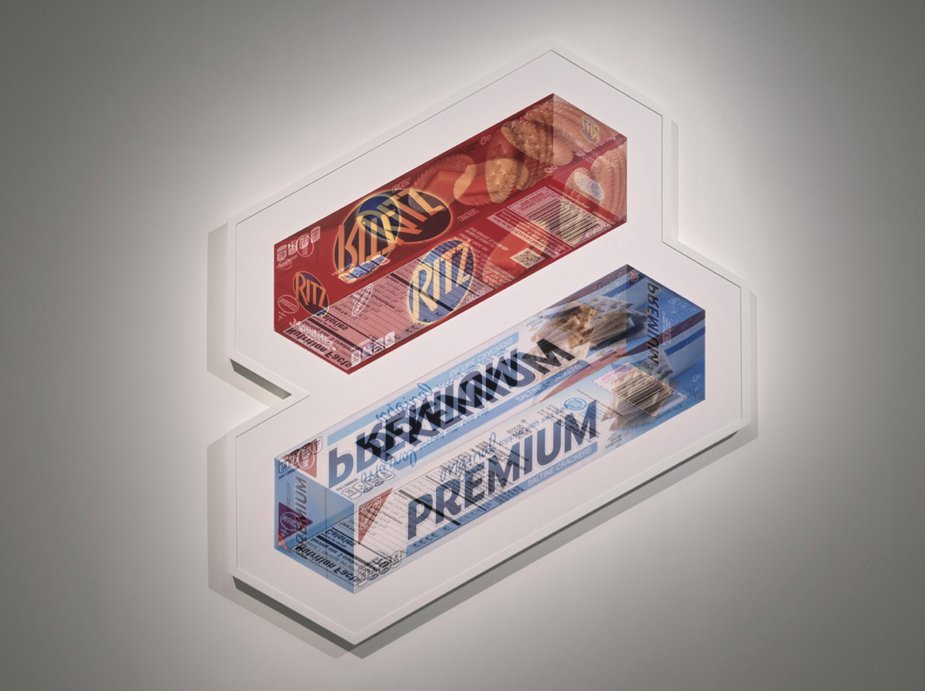

The objects represented in your works on show in Experimental Photography are what I call “ostensible”. In Ritz and Premium and It’s-It and It’s-It, you work with food packaging and in Photoshop and Photoshop it’s the packaging of Adobe Photoshop, perhaps the default image-making medium of this century so far. I really like the straight comparison that having these three works in the same physical space prompts – the idea of both image software and savory crackers as off-the-shelf, basic goods of daily life, given distinction by the branding of their packaging design, and given form by the volume of a box, which we know from our experiences of opening such boxes contains a lot of thin air within it! Can you say more about what these “ostensible” objects are for you?

Brandon Lattu:

I think they are spectres – apparitions – of the system of exchange that surrounds them. My enthusiasm for the container is almost entirely divorced from the actual product purchased. I am sure that I am not alone in having bought things purely because of the delicious visual aesthetic that surrounds them. But maybe that’s too vague. Ritz and Premium are superlatives that mean the best, and who doesn’t want the best, even if it is delivered on a lowly cracker, right? It’s-It and It’s-It is about goo and unknowing and primordial ooze; the perfect confection of iced cream dripping down everyone’s chin and chocolate slathered up their arm. They couldn’t even come up with a name for the product! That said, their box is one of the most beautiful selections one can make from the 40,000 odd items the average U.S. supermarket offers. I’ve been making these images of product containers since 2001, and almost all of them have been consumables. Photoshop and Photoshop is a new direction and the newest of these works. It’s a bit like explaining to a child that music used to come on a disc and photographs were contained on film – but in reverse. It’s downright odd to imagine software, the product par excellence of the so-called information economy, as needing a material presence for a consumer to exchange money to receive it. In fact, soon after these editions, Photoshop moved to all digital distribution.